City of Gaze: Jeong Jeong-ju

Interview – Familiar Strangeness, Jeong Jeong-ju’s Urban Experience in Art

Solo Exhibition <City of Gaze>

gallerychosun

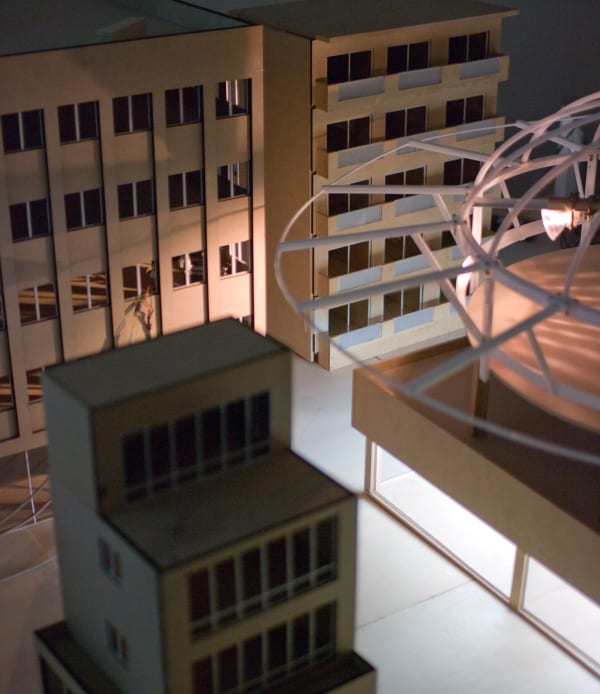

Jeong Jeong-ju: To briefly introduce my work, I construct architectural models of buildings, install a moving camera within their empty interiors, and then present video footage that captures both the interior of the model and the exterior space of the exhibition environment where the work is displayed. In earlier works, the models were based on real places with which I had a personal connection; like the living room of my own home or a shopping mall in Ilsan I passed by daily. In those cases, there was a direct and emotional relationship between myself and the architecture I was representing. But over time, I began working with unfamiliar urban spaces like cities in Japan and China. Those which I had no connections with. As a result, the sense of reality within the models began to fade. My exhibitions until now were about the “City of Gaze”, but the theme for my upcoming solo exhibition at the Kim Chong Yung museum will be “Illusion”. I believe this shift reflects the changes in how I perceive and relate to the spaces I reconstruct.

Sumi Kang: After hearing what you’ve said, I think it makes sense to start with a basic question. How do you define “city” in your work?

JJ: My first creation about the city as a collective subject was <덕이동 로데오 거리> (2006). When I first visited the area, I immediately thought “I need to recreate this”, and began working on a model. Then, when I was preparing an exhibition in Shanghai, I built <Zendai Plaza> which had been redeveloped as a massive shopping complex. The museum which the exhibition was held in was also a part of Zendai Plaza. It was around that time that my interest in the idea of the city really deepened. Especially after reading a newspaper article in China about so-called “mirage cities”. Apparently these enormous mirages sometimes appear over the sea of China’s western coast. Huge cities rising from the ocean and disappearing within hours. After installing the <Zendai Plaza>, I began to feel that cities, in a way, are like mirages themselves.

SK: If I try to interpret your experience here, it seems that your first impression of the city was something like a mirage, a view of the city as an environment. Thinking of it in relation to how you, Jeong, might visualise your own work, it may be something like this. The city, as a physical entity, is grounded and material. But over time, that sense of substance fades. The weight and volume disappear, and what’s left is just the appearance. The city exists only as an outer shell. It’s like a thin, fragile skin, perhaps similar to the delicate silk houses made by artist Suh Do Ho. Am I on the right track?

JJ: I find it hard to clearly define the vision of the city I have in mind. That’s why I’ve been working without locking myself into any fixed conclusion. When I was preparing for the exhibition <City of Gaze>, I didn’t have a plan other than to build a lot of buildings. It started in 1997 with my solo show in Japan, where I began making models of houses near the Nagoya exhibition site that were set to be demolished due to redevelopment. Later, while preparing for the exhibition in Shanghai and for this exhibition, I started including buildings from places like Ilsan in Korea and the so-called “UFO buildings” in Shanghai, along with smaller-scale buildings. At some point, I realised I had started to develop certain criteria for choosing which buildings to model. The works in Japan, for instance, included a lot of private spaces. Soon after, the scale grew, and I began creating many empty buildings. In any case, walking through cities and observing them has become a continuous part of the process. Selecting buildings, turning them into models, and setting up cameras all incorporate my personal experiences and memories in a more concrete way. I think my experience in the city surfaces in the work. A kind of numbness of disconnection. Not so much in terms of human relationships, but more like a sensory confusion.

SK: I found your work from 2006, based on Deogi-dong Ilsan, really interesting. The architectural model of a shopping mall you created didn’t quite fit the label of “multinational architecture”. It felt more complex and strange, which, in a way, reflected the identity of Ilsan as a planned city. But what’s striking about your work isn’t just the building models. The video projections outside of them also feel mysterious . The UFO shaped models, like something out of a sci-fi film, and the footage captured by tiny cameras moving inside them create a powerful, almost hallucinatory space. Are you trying to take that idea even further with this new work?

JJ: Right now, the models I have laid out in my studio include buildings I collected and recreated from Nagoya in Japan, others from Korea, and some from Shanghai. Starting with my solo exhibition in China, I began thinking about creating a kind of “situation”. At first, this took shape through the use of rotating lights. The UFO shaped buildings slowly rotate while casting a strong beam of light. The light filters through the windows of nearby models and shines their interiors. Inside those models, small cameras capture the shifting light, and the footage is projected outside again. The result is a fragmented sweep of light that flashes across the space. Similar to how a passing car’s headlights briefly illuminate a building at night.

SK: It’s motion. The motion of light.

SK: What I find interesting is that your work focuses on the city in a paralyzed state. When it loses its function and exists only as a physical space. From what I remember, during your shows in Nagoya and Shanghai, you weren’t necessarily thinking along these lines yet. Back then, the emphasis seemed more on the relationships between buildings. For example, someone inside looking out, versus, an outside gaze curious about what’s inside a particular home. But now, what you’re talking about feels much more like a kind of cultural critique. It reminds me of the phenomenon that occurs as cities become increasingly industrialised; what we might call the “hollowing out” of urban centers. That sense of crisis could become a powerful narrative in your work. And when I say “hollowing out”, I don’t just mean the physical departure of people or the rise of bedroom towns. I’m also talking about cities that have lost their inner and outer functions, remaining only as material shells. It’s not just about the absence of people, but the absence of purpose. And I get the sense that you’re interested in the psychological state of the city dwellers when their environment becomes that kind of hollow space.

JJ: Yes, it’s like that moment when you suddenly cover your ears and everything feels muffled. A sudden emptiness. A kind of paralysis. That’s how I would describe the psychological state of an emptying city.

SK: Let’s expand on the idea of the “paralyzed city” that you mentioned, and the “hollowing out of the city” that I brought up earlier. When we hear “paralyzed”, we tend to think first of a kind of physical stoppage, which can feel one dimensional. But when a city becomes empty, it’s more than that. It’s the loss of the city’s identity. And what’s crucial in your work is how you render that loss into something the viewer can actually perceive. It’s not just about evoking fear or crisis. That alone doesn’t quite capture it. What your installations seem to offer is something stranger. The uncanny. The unsettling fear that arises when something familiar becomes unfamiliar. Through your city-based installations, the audience experiences that psychological dissonance firsthand. I think that’s something worth emphasizing more: the sense of a latent danger embedded in the everyday city. Something that only reveals itself through your work, almost as a kind of premonition.

Interview by Sumi Kang

Sumi Kang holds a PhD in philosophy and is a research fellow at the Institute of Humanities at Seoul National University, where she also teaches. She is an aesthetician and art critic. Her publications include <서울생활의 발견>, and <한국미술의 원더풀 리얼리티>, and she has written extensively on the aesthetics of Walter Benjamin. As an independent curator, she organised the exhibition <번역에 저항한다>, which received the “Artist of the Year” award in 2005.

This text is excerpted from the “Young Artist 2010” feature in the January 2010 issue of <Culture + Seoul> published by the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture Magazine.